Case Study: Why Secure KS3 Foundations Matter: Building Sentence Control for (I)GCSE Success

- Silvia Bastow

- 10 minutes ago

- 6 min read

This blog post was written by Céline Courenq.

About the author of the post:

Céline Courenq is Head of World Languages (MFL and Home Languages) at a British international school in Bangkok, leading language pathways across KS3–IB She previously taught in comprehensive secondary schools in the UK, which continues to shape her commitment to inclusive practice and strong foundations. She has led the implementation of the EPI model across KS3 and KS4, is EPI accredited, and is also an IB examiner. Celine has organised EPI/Dr Conti-focused workshops through FOBISIA and has welcomed colleagues from other international schools for collaborative curriculum and practice-sharing. Her interests include curriculum coherence, cumulative retrieval, and the link between KS3 foundations and external assessment outcomes.

In an inclusive, high-performing international context, language learning can look fine on the surface. Students are articulate, confident, and often multilingual. They participate readily and generally cope well with demanding tasks. Yet in our context, despite strong academic ambition, (I)GCSE outcomes began to reveal something we could no longer ignore: students were reaching Key Stage 4 with gaps in sentence-level control, grammatical accuracy, and

spontaneous fluency.

When confidence masks fragility

Our student body includes a wide range of learner profiles. Behaviour is excellent, motivation is generally high, and verbal reasoning skills are often strong. Many students have experience of more than one language.

But confidence is not the same thing as control. Students could infer meaning from context, sound fluent in familiar routines, and produce work that looked “successful” in the moment, yet lacked automatisation of high-frequency language. Over time, that created a gap between what they understood and what they could reliably produce, especially under pressure.

What finally made it undeniable was Year 10: students arriving with shaky control of verbs you simply can’t do without.

We kept seeing the same thing, students who had apparently been “fine” for years, but who could not manipulate core verbs such as avoir with confidence. That isn’t a KS4 problem but a foundation issue that has been allowed to sit quietly for too long.

Rethinking what KS3 is for

KS3 had drifted into “exposure and enjoyment”: lots of content, lots of reassurance, not enough cumulative security. Curriculum time was at times irregular, contact was sometimes non-consecutive, and there was a natural tendency to prioritise confidence over precision, particularly in contexts where everyone wants students to feel good about learning.

Confidence built on insecure language doesn’t survive exam conditions. Without systematic recycling, retrieval, and sentence-level practice, early misconceptions fossilise. Students move forward with a sense of fluency that is, in reality, fragile. Once (I)GCSE introduces clearer success criteria and external benchmarking, those weaknesses can’t be smoothed over.

What changed in practice

At curriculum level, we have adopted an evidence-informed instructional framework (EPI) , moving from topic-led schemes to skill- and structure-driven sequencing. Each unit is built around a small number of core sentence patterns and grammatical features, selected for frequency and long-term utility. These are treated as non-negotiables: students are expected to retrieve them fluently before moving on.

At both KS3 and KS4, sentence builders and knowledge organisers became central as a way of making the taught language concrete and retrievable. Examination board specifications provide vocabulary and grammar lists, but those lists are reference points, not an instructional plan. In practice, we introduced vocabulary through carefully selected sentence-level constructions, chosen for frequency, transferability, and grammatical leverage, and revisited them systematically over time.

Rather than presenting lexis as isolated lists, we embedded vocabulary in chunks that students could immediately manipulate. Knowledge organisers stabilised this core language across units and year groups, so learning didn’t “reset” after an end-of-unit test. The goal was not to cover more content but to make fewer structures usable under pressure.

Pronunciation, previously an inconsistent area in French, also had to be tackled properly. We embedded a structured phonics approach from KS3 onwards, because if students can’t reliably map sound to spelling (and vice versa), everything else becomes harder: listening, reading, and the confidence to speak.

Assessment practices shifted too. Instead of relying mainly on summative judgements, we built in frequent low-stakes checks and formative checkpoints to make learning visible early. That meant gaps were identified while they were still fixable, rather than being discovered at the point where they start damaging KS4 outcomes.

PHOTO 1-Sentence builders used to secure a small set of high-frequency constructions

PHOTO 2 -extract from a Knowledge Organiser for Year 7 French

Coherence across the key stage: non-negotiables and cumulative retrieval

To sustain consistency across classes and year groups, each year group worked with a small set of clearly defined non-negotiables. These articulated the core language and structures that all students were expected to retrieve fluently by the end of the year.

Importantly, these were not treated as one-off endpoints. They were deliberately revisited and retrieved across subsequent units and year groups. That shifted progression from linear “coverage” to cumulative security. Language introduced in Year 7 did not disappear once assessed. It stayed active through systematic retrieval in Year 8 and beyond.

Teachers retained autonomy over pacing and classroom decision-making, but the non-negotiables provided a shared reference point that reduced drift, made gaps visible early, and ensured continuity.

A KS3–KS4 causality example

The clearest evidence for the impact of earlier curriculum decisions showed up not in headline grades, but in the types of errors students made under exam pressure. Patterns that looked like “KS4 issues” were often the predictable outcome of gaps in automatisation at KS3, especially where French structures don’t map neatly onto English.

A simple but revealing example is the French perfect tense. Historically, many students defaulted to an English-transfer model-treating the past as either a direct translation (je jouer) or as a single “have + verb” pattern, without securely controlling auxiliary choice, past participle formation, and agreement. Under pressure, this produced predictable errors such as je jouer instead of j’ai joué, j’ai allé / je allé instead of je suis allé(e), and inconsistent

participle endings even when students could recognise the correct forms receptively.

By securing the underlying constructions earlier, high-frequency avoir verbs in the perfect tense, the limited set of verbs that take être, and the agreement logic, students became markedly more reliable in both accuracy and fluency. The difference was not increased exam practice in KS4, but earlier automatisation of structures that do not map neatly onto English. This kind of error pattern is not a knowledge gap so much as a control gap and exam conditions are designed to expose control.

In other words, underperformance was rarely caused by a lack of ambition or vocabulary, but by a lack of control of high-frequency structures when scaffolds fell away.

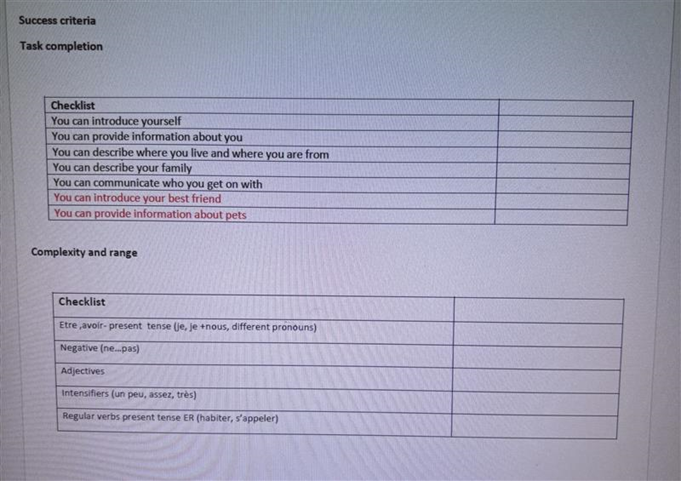

Success criteria snippet showing focus on completion and complexity/range

Impact and emerging evidence

The change has been visible in students' written work, in speaking, and in the kind of mistakes that have all but disappeared. Notably, the impact has been most immediately visible among students who previously relied heavily on confidence, memory, or teacher scaffolding to “get by”. As expectations became clearer and retrieval routines more

consistent, these learners showed particularly strong gains in accuracy and independence, suggesting that the approach reduced hidden barriers and made success more attainable for a wider range of students.

More broadly, students show greater consistency in written work, increased confidence in spontaneous speaking, and a clearer grasp of the structures they are using. Importantly, they can explain why a sentence works, not simply whether it “sounds right”.

(I)GCSE outcomes over the past two years have reflected this increased security, with more consistent performance across cohorts. Many variables influence results, but the alignment between KS3 foundations and KS4 demands has become markedly stronger.

Equally significant has been the impact on teacher practice. Shared frameworks and clear non-negotiables improved coherence across the department, reduced variability, and strengthened collective accountability without undermining professional judgement.

Reflections for similar contexts

In high-performing international settings, it is tempting to assume language learning will take care of itself. Our experience suggests the opposite. Precisely because students are articulate and confident, gaps can remain hidden until external assessment makes demands explicit.

By prioritising depth over breadth, and automatisation over exposure, we have been able to support learners more effectively while maintaining high expectations.

This approach is not about lowering demands or over-structuring learning. It is about recognising the cognitive realities of language acquisition and designing a curriculum that respect them. In doing so, we have begun to reposition language learning as a serious academic discipline, rather than a subject that relies on confidence and presentation.

Looking ahead

Our next steps involve further embedding sentence builders and knowledge organisers at KS4, refining assessment alignment, and continuing to use evidence to inform intervention. Although the examples in this piece are drawn from French, we are now adapting the same principles across other languages in our department. The approach transfers, but the points of difficulty differ by language: French demands systematic attention to sound–spelling relationships; German often exposes gaps through case and word order; and languages such as Japanese and Mandarin introduce additional challenges around script, phonology, and how learners segment and retrieve language. For that reason, the methodology is being applied consistently, while the linguistic focus is tailored.

When KS3 is treated as intellectually rigorous and structurally sound, KS4 outcomes follow. EPI provided the framework to make that connection explicit and, most importantly, effective.

Comments